Playing Popular Science: Presentation from 1st Joint International Conference of DiGRA and FDG

A landmark conference was hosted in Dundee this year which saw the two research groups, DiGRA and FDG, come together to sharer research and practice in the field of games. At the 1st Joint International Conference of DiGRA and FDG (2016), I was fortunate enough to discuss Project:Filter in a session titled "Playing Popular Science", organised by Dr Robin Sloan of Abertay University. I thought it would be a good idea to upload my presentation from the conference for those who may still have been interested but decided to attend a different session, or even for those who may not have attended the event.

Presenting "Project:Filter, Design and Experimentation" to the session audience.

The presentation can be seen below, but I also want to give a special mention to the four student teams from Abertay University that also presented their games. I was very impressed by the level of work that they have delivered and how they have shown the potential that games have in non-traditional areas.

Quantessential Games have worked with Dr Erik Gauger of Herriot-Watt University on the idea of quantum mechanics. Their prototype, Orbs, makes sense of a very complex (and theoretical) subject in a puzzle-platforming format. Players must manipulate the environment to change the state of two orbs, which can then be used to solve puzzles. Fire and ice, and static and non-static contrasts were shown as required states to complete certain puzzles. Watching the prototype play out, I was reminded of Portal's puzzling mixed with the comical narrative tone seen in Firewatch. I hope Quantessential Games continue their development on Orbs as they mentioned.

Benthos Games presented Tides: A Shark's Tale, in partnership with the Scottish Crucible. The students worked alongside Dr Helen Dooley, an immunologist and self-professed shark-lover from Aberdeen University. This game has players controlling a cat shark through polluted waters, and becoming emotionally attached to other sharks that have become distressed by their changing environment. It shares many similarities with Polluted, particularly its 2D-adventure and narrative-driven elements, which had me pondering standardisation of practice for serious games, and whether this is possible.

Crowbar Games created Namaka, a delightful 2D-adventure game along a similar style to Tides. They addressed the issues of microplastic pollution through a series of mini-games plotted around the environment, and subtle aesthetical evolutions during the play session. Crowbar Games worked alongside Microsoft, which also saw their involvement within this year's Imagine Cup competition. Not only has Namaka been a success for the student team, but they have also been competing in this year's Dare to be Digital competition. It's nice to see teams sticking together to continue on new projects, and I wish them all the best with their participation in Dare!

Finally, we have Cell Cycle from Type 3 Games, in collaboration with Dr Adrian Saurin of Dundee University. This hex-grid strategy game sheds light on cell divisions, with just the right level of subtle context surrounding cancerous cells. Out of all the games presented (Project:Filter included), Cell Cycle looked the game most-ready to be released for the market. It looked simple, clean, and has a responsive strategy system embedded.

Having gone through the same process as an undergraduate, and knowing the level of dedication and work required for the coursework, I tip my hat off to everyone. The students from Abertay University have highlighted more potential in using games to address social and scientific enquiries, and I look forward to seeing these projects come forward.

My presentation from this session, with commentary, can be viewed below. Please do get in contact if you have questions / comments / suggestions / feedback!

Project:Filter, Design and Experimentation

My interest is in so-called “serious games” as a method for public intervention. Today, I want to talk about how game design and experimentation work together and inform each other. I’ll be briefly discussing a research project called noPILLS, which I’m basing my work upon, before discussing Project:Filter and a few pre-studies that have informed its development.

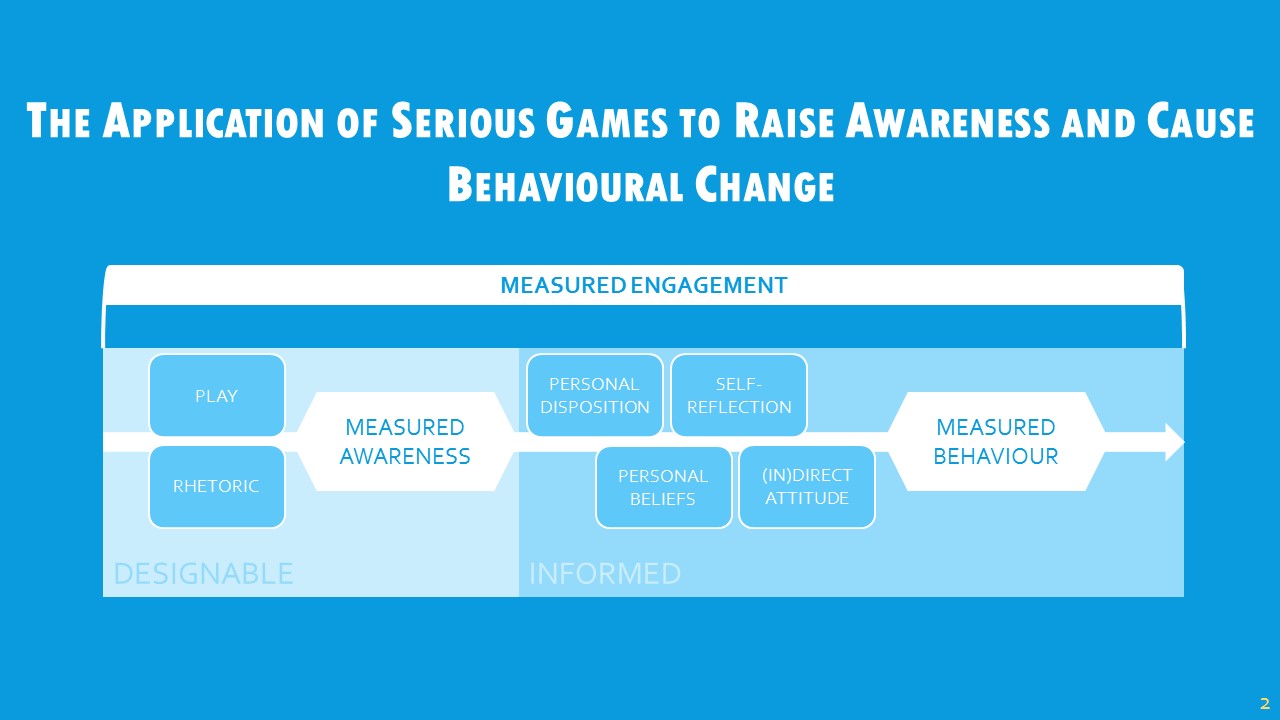

I’ve been looking to address this topic of applying serious games to raise awareness and cause behavioural change. Essentially, I’m looking to uncover ways in which to design and develop games intended as a public intervention method, and how we can measure things like awareness and behaviour through games. This model is something I’m playing around with at the moment, which considers elements of the game experience that are both designable and informed. When I say “designable”, I refer to things that can be controlled by the developer, like mechanics. What I mean by “informed” is those parts that cannot be controlled, and generally refer to the player’s sense of “self” which affects their experience of the game. Developers can attempt to create an intended experience, but I would argue that experiences are individualistic because of the player’s disposition, their beliefs and so on. I thought it was important to consider this at first, and I think there’s something relating to haptic experience there, where perception of content rather than the content itself informs action; that’s something I’d like to look at later on.

These words (awareness, behaviour, and engagement) are very loaded and vague terms, even within their own domains. It’s been quite tricky to talk about games as a method of intervention without at least trying to define these terms, and highlight what and how I want to achieve certain things. I would consider this an end goal to my PhD, to define what these terms mean to us as developers, and so I’d love to discuss this with you.

As I mentioned, my work is based on noPILLS, a pan-European research project that highlighted the challenges and severity of micropollution. The games on the screen are two examples made from the noPILLS Jam which Glasgow Caledonian University hosted in 2014: Sewer Sweeper is a rail shooter that has players shooting pollutants within water pipes; and Polluted is the adventure of a fish that must hide from its aggressive peers in order to escape the polluted waters. These games have been really useful to show off to the public and gauge what it is they like about each game, but it hasn’t really helped me in understanding the holistic process design and development of serious games for public intervention. This has prompted me to develop my own game, drawing upon these examples for inspiration.

What I’ve come up with is Project:Filter. It is designed for schoolchildren at the Formal Operational learning stage (from Piaget’s learning theory), so around 12-13 years old. Players control a small drone that has been tasked with collecting micropollutants from pipes within the filtering system. Project:Filter highlights the causes of micropollution, and the knock-on effects from associated challenges through small anecdotes that players unlock. Filters spawn periodically to help the player clean the waters, but over time these filters become less frequent and micropollutants spawn more often, adding a scaled element of challenge similar to that of Tetris. This is also intended to give the player a sense of empowerment, as they become less reliant on the filters. The game ends if players lose all their lives, or the filter loses all of its health. The game is intended to be a launching pad for discussion about water pollution, and I’m hoping to work with schools to incorporate this into a wider curriculum project. I have a little book here that I would ask you kindly to leave any comments you have on Project:Filter – because, unfortunately, I have a memory like a sieve…

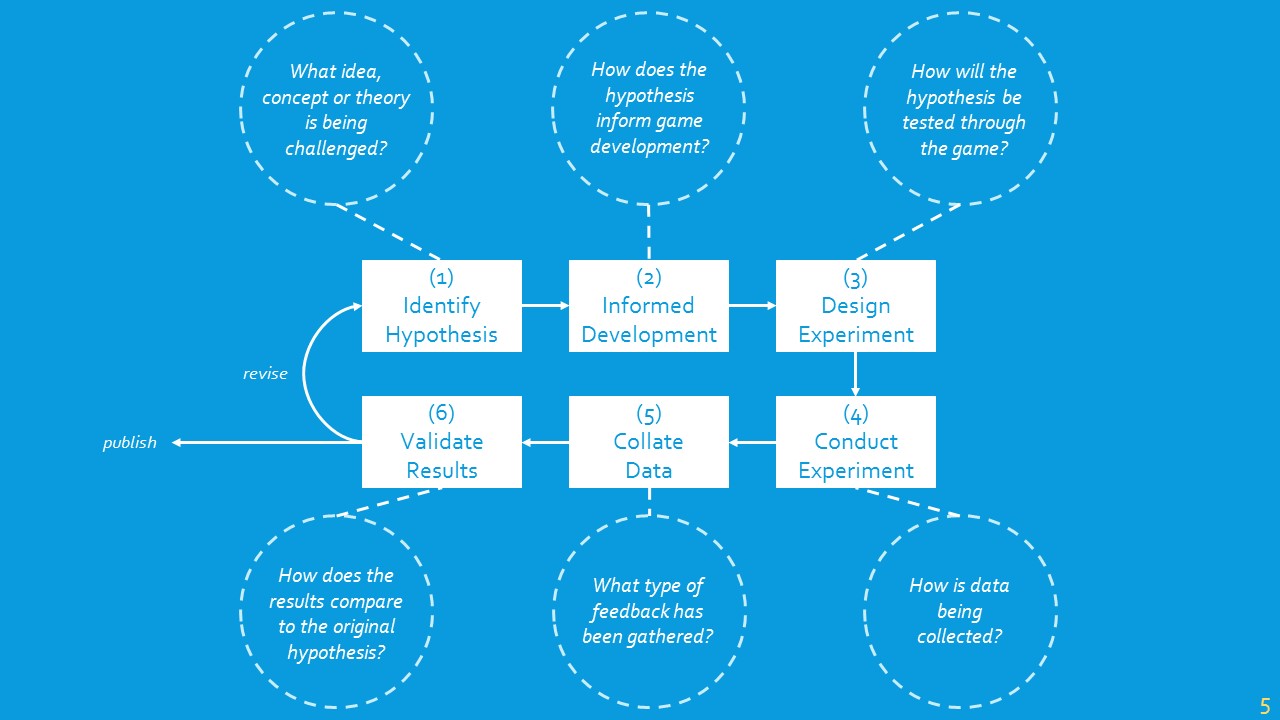

I mentioned at the start of this presentation that I’m interested in how experiment design informs serious game development. This is the model that I’m looking to follow. I took a lot of inspiration from Mary Flanagan’s Critical Play framework, which has had a major influence over my work. To generalise it, it’s a fairly straightforward framework that cycles between ‘Develop’ and ‘Test’, there’s nothing overly-complex. But it’s been useful to follow and to focus efforts in one area at a time.

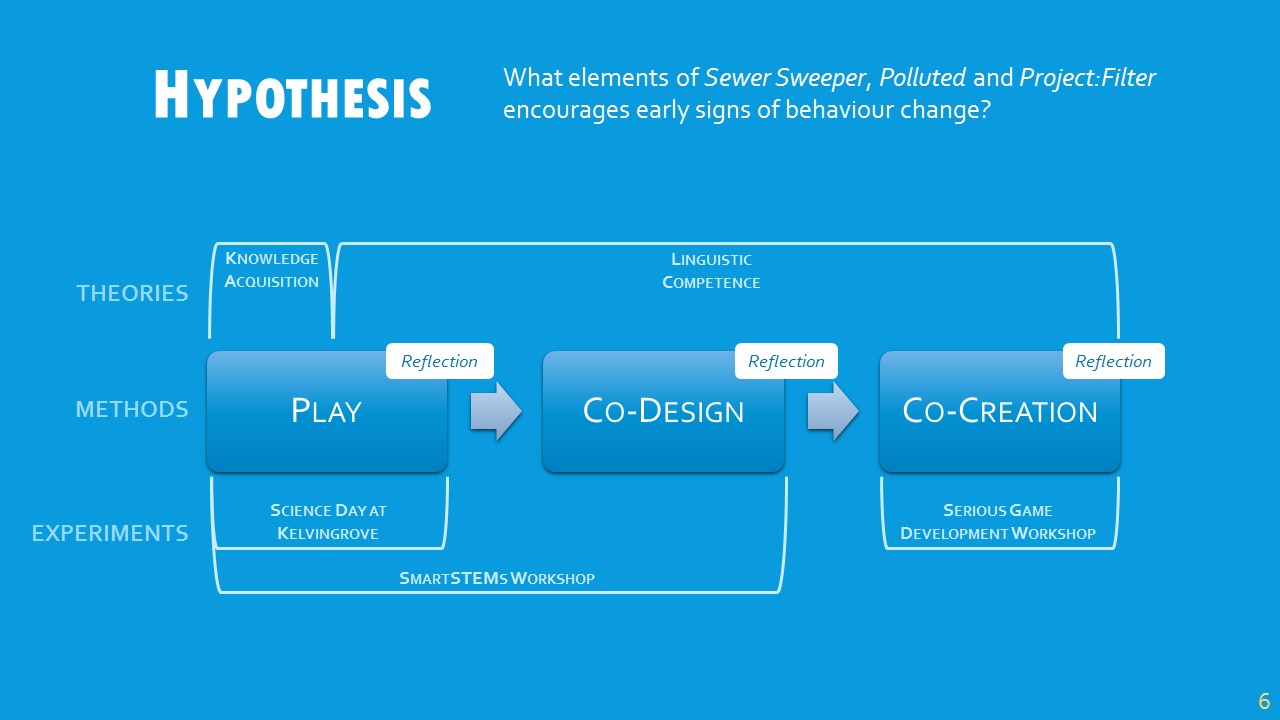

I’ve conduct three pre-studies using the games from noPILLS and my own. What I wanted to uncover was whether each of the three games could encourage precursory exhibitions of behaviour change. I’ve identified two stages of behavioural traits to test: Knowledge Acquisition and Linguistic Competence. Basically, I wanted to find out if players learned enough about water health from the games to then be able to design and develop games of their own in the same context. I conducted three pre-studies that looked as specific parts of the overall experiment. This was essentially a trial run to test the logistics of the experiments and make changes before running this as a full experiment.

The first pre-study was a design workshop as part of our SmartSTEMs Day at Glasgow Caledonian University, where female schoolchildren were invited to participate in STEM-related subjects. There were three short workshops throughout the day: the schoolchildren played each of the three games, then were put into small groups and challenged with designing a water health game. The games that were designed were expected to show knowledge taken from the games, as well as the ability to take this knowledge and apply it to a specific context, in this case game design. My rationale from this is that game development engaged the schoolchildren in understanding the complexities of a fairly-challenging topic, and we can see as a result the variety of their designs. Most commonly, games went along the lines of very popular games among the groups, such as Subway Surfers, with the context of water pollution embedded within the design, which was a successful outcome in my opinion.

The second pre-study was a public demonstration at the Glasgow Science Festival at Kelvingrove Art Gallery. This was a two-day event that highlighted play within a situated environment. It allowed me to test how well each of the games would do within a public environment such as a museum, particularly as digital curation and interaction has become a rapidly-developing area for public galleries and museums. The audience was predominantly young children, and I’d say that Sewer Sweeper and Project:Filter was too hard for most of them. But Polluted did really well, mostly because they could follow the story along with it. What made this more interesting was the filter demonstration set up with it. The children moved round the tables anti-clockwise, so by the time they got to the games they already had a demonstration of why filtering is important, and what micropollution is. So when it came to playing the games, the children and parents were pointing out these things to each other, relating their in-game experience to the live demonstration. It helped the players to comprehend the issues and challenges associated with the topic of water health.

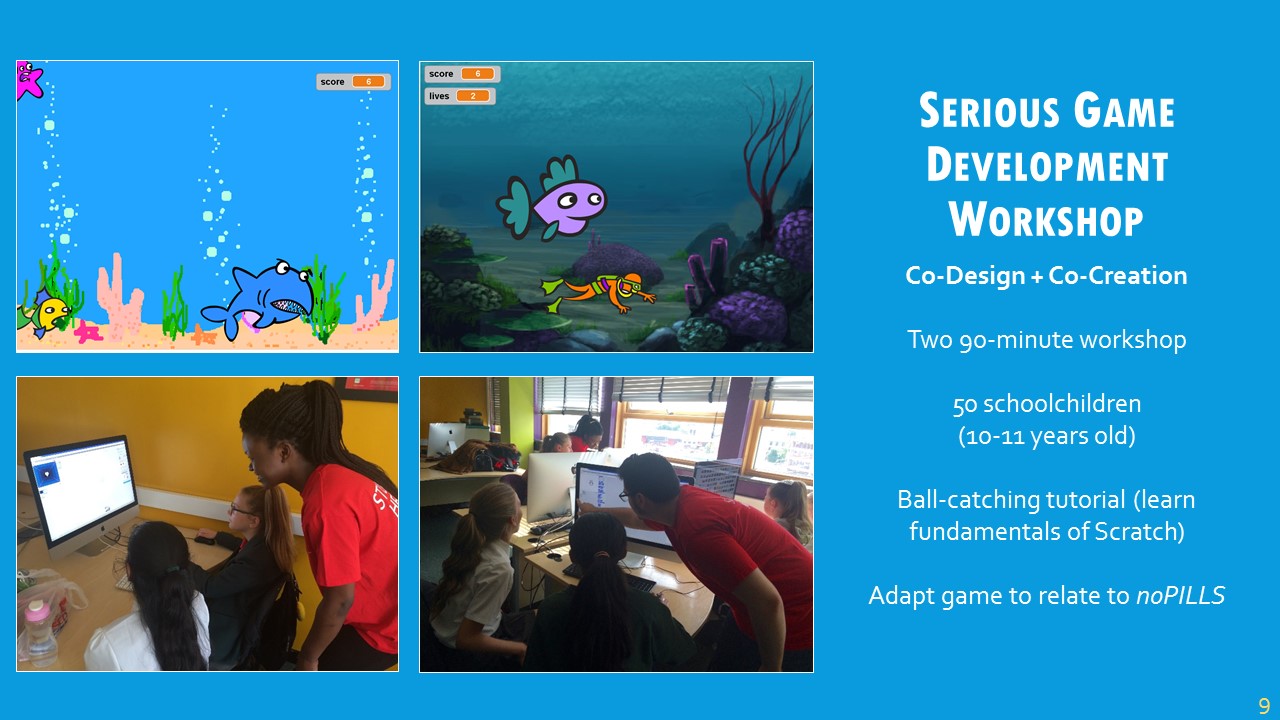

The third and final pre-study involved Scratch development. Two workshops were run with 50 schoolchildren aged 10-11 learning how to make games. Pupils were put into pairs and had assistance from various student helpers. The workshop was set up to follow the ball-catching tutorial as part of the resources with Scratch. Afterwards, they were challenged to change the look of the game and add new features to relate the game to water health. It was relatively successful, but not too many games were made with water health in mind, these being two of very few. As this was the first time these pupils had used Scratch before, they were more eager to learn how to do different things with the block-code, rather than think about the “serious” aspect of making a serious game. I think the workshop would be better-supported when it’s run with other aspects of the experiment, which is the next stage of my research – to bring each of the workshops together into a full-day experiment.

This research is still ongoing, and I’m always relatively anxious to find out what others think, but I’m always open and eager to any feedback and comments. Thank you!